In competitive Scrabble, there’s Nigel Richards and everyone else. The 57-year-old New Zealander has won 11 North American and world championships combined; no one else has won more than three. He is widely believed to have memorized the entire international-English Scrabble lexicon, more than 280,000 words. He crafts strategic sequences that outperform the best bots. He’s a gentle, mild-mannered, private, witty, unflappable enigma—the undisputed Scrabble GOAT, and one of the most dominant players of any game ever.

Nigel—one name, like Serena or Michelangelo—went viral in 2015 after winning the French world championship even though he didn’t speak French. He inhaled some large chunk of the 386,000 words on the Francophone list, and did it in a mind-boggling nine weeks. That same year, he won a tournament in Bangalore, India, with a 30-3 record. In one of those games, Nigel extended ZAP to ZAPATEADOS (the plural of a Latin American dance). In another, he threaded ASAFETIDA (a resin used in Indian cooking) through the F and the D. Those words likely had never been played in Scrabble before, and likely won’t be again.

In late January, Nigel returned to Bangalore, and this time he out-Nigeled himself. Here’s what happened. Round 3 of the four-day event, held in the cafeteria of a data analytics firm, matched Nigel against a longtime Indian player, Rajiv Antao. After a few low-scoring moves, Antao dropped the game’s first bingo, a play using all seven tiles and netting a 50-point bonus: LOOTERS. The placement dangled the L in the triple-word-score column. When Antao didn’t block the risky spot on his next turn, Nigel laid down INFLUXES through the L, covering two triple-word squares at once, a play known as a triple-triple or nine-timer. It scored 221 points.

“The game was over right there,” Antao told me in an email. “But not for Nigel.”

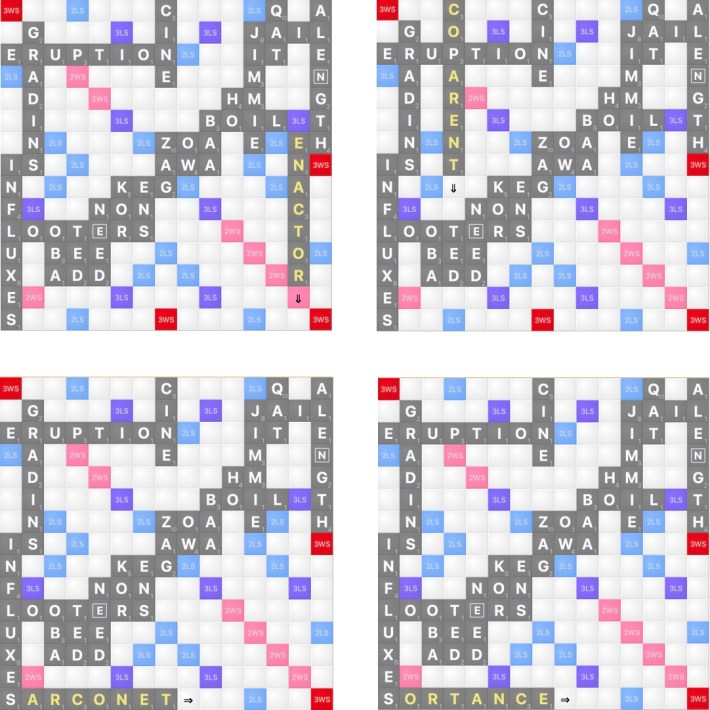

Nigel’s three subsequent moves were also bingos: GRADINS (a series of steps), ALENGTH (a full length), and ERUPTION. “I was a spectator,” Antao said. After his next play, the score was 583-237. Here’s how the board looked:

Nigel now held the letters ACENORT (Scrabble players often arrange their letters in alphabetical order). The only seven-letter word in that rack, ENACTOR, played for 70 points. But three eight-letter words scored more: COPARENT for 82, SORTANCE (an obsolete word meaning suitableness) for 83, and SARCONET (a silk fabric) for 89. A good player would spot all of those. Nigel’s fifth consecutive bingo was guaranteed.

But Nigel didn’t play any of those words. Look at the board again. Find the P in ERUPTION. Count the number of squares down to TED (to spread hay for drying). There are seven, the same number as tiles on a rack. Then look one square up and one square over from the T in TED—the word NON. Nigel placed all of his letters between the P and TED, spelling out PERNOCTATED and turning NON into ANON. The play tallied 92 points. In Scrabble notation, it’s represented like this: (P)ERNOCTA(TED).

That’s a bloodless way to describe the play. Here are some other ways: The Exploding Head Emoji. John McEnroe screaming “YOU CANNOT BE SERIOUS!” Holy fucking shit! This ridiculously obscure 11-letter word formed by sandwiching a bunch of letters between a bunch of other letters captures everything that makes Scrabble so addictive to tournament players like me and compelling to obsessives who play and watch livestreams and videos online. (P)ERNOCTA(TED) is a dizzying feat not only of anagramming and word knowledge but of spatial relations, visual awareness, imagination, creativity, and sangfroid. It is, in its own way, art.

News of Nigel’s play quickly spread around the world, literally. After the game, Antao posted a photo of the board in a WhatsApp group for players at the tournament. Another player dropped it in a Singaporean Scrabble chat. Someone there shared it in Scrabble groups on Facebook. At a tournament in Sydney, Australia, “it was all anyone was talking about,” veteran player Howard Warner of New Zealand said. “Wowsers!!” one player wrote on Facebook. “It’s simply frightening,” said another.

Josh Sokol, the current North American champion, told me that (P)ERNOCTA(TED) is even more than that: “Possibly the best play of all time.”

At a time when artificial intelligence has assumed overlord status in the popular imagination, Nigel is a reminder of the unknown limits of human performance and the mysteries of the human mind. His feats of raw memory, linguistic magic, and strategic perspicacity—turning REALISM into HYPERREALISM and WITNESS into EARWITNESS; outfoxing opponents to steal seemingly hopeless games with intricate, multi-turn setups—are recounted among Scrabblers with awe and wonder.

And not an insignificant amount of attention, for a Scrabble player anyway. A German champion, Alex Dings, recently made a 49-minute video documenting Nigel’s prowess that’s closing in on 800,000 views. Will Anderson, the 2017 North American champ, has produced 10 videos about Nigel with more than 3 million views combined; one of them, “The Greatest Scrabble Player Ever Is Underrated,” alone has more than 1.7 million views. Commenters on Anderson’s YouTube channel have a catchphrase: “I see Nigel, I click.”

(P)ERNOCTA(TED) is the latest example of why Nigel even has memes. Pernoctate means to pass the night in vigil or prayer. It’s derived from Latin. The very few Google hits that aren’t about the word’s definition or etymology include floor-mop-haired ex-British prime minister Boris Johnson showing off his vocabulary and a book about Etruscan cities and cemeteries published in 1848. (“Let no one conceive that he may pernoctate at the Ponte della Badia with impunity.”)

Meanings don’t matter in Scrabble. Competitive players care only whether letters arranged in a particular order are acceptable in whatever lexicon governs play. The dictionary is a rulebook. Learn more rules, score more points, win more games. Scrabble is about pattern recognition; players use anagramming websites and software like Aerolith and Zyzzyva to study and memorize thousands of letter strings. The very best learn all of the seven- and eight-letter words, because those account for the overwhelming majority of bingos played. Scrabble’s international word list, published by the British dictionary-maker Collins, contains more than 34,000 sevens and 42,000 eights. That’s a mind-jamming number of patterns to keep straight.

The returns on memorizing words longer than eight letters diminish rapidly; they just aren’t playable often enough to justify the study time or brain space. While a few top players try to learn the nine-letter words—almost 43,000 on the Collins list—pernoctate is a 10-letter word, and pernoctated is an 11. The only way for a Scrabble player to know this fancy old word—which, like the aforementioned ALENGTH, SORTANCE, SARCONET, and NON, isn’t on the slimmer word lists governing play in North America—is to have studied it. Nigel knew the word. Ergo, Nigel had studied the word. Ergo, Nigel knows the 10-letter words, and probably the 11s, too, and likely more.

“Until proven otherwise, we have to assume that Nigel knows every word in the dictionary, regardless of length, and that he’s achieved feats of memory most of us could only dream of,” Anderson says in a video about (P)ERNOCTA(TED). Another superexpert, Austin Shin, who recently faced off against YouTube’s The Try Guys, pointed out that if Nigel has indeed memorized every acceptable word, that means he knows more than twice as many words as his rivals, and anyone else in the 40-plus years since Scrabble contested its first championship.

The legend of Nigel began in picturesque Christchurch, a city of 400,000 on New Zealand’s South Island.

As a toddler, Nigel was interested in numbers rather than words, his mother, Adrienne Fischer, told the Sunday Star-Times of Auckland in 2010. “He used to point to the calendars,” Fischer said. “He related everything to numbers. We just thought it was normal.” School was easy. “They’d put stuff up on the blackboard, I’d read it and wouldn’t need to study it again,” Nigel told me at the world championship in Melbourne, Australia, in 1999, when I was reporting my book Word Freak about the subculture of competitive Scrabble. Nigel played a lot of video games in high school. He turned down a university scholarship. He was “too lazy” for college, he said, “too laid back.”

Nigel maintained printers for banks and repaired pumps for the city water department. He became a long-distance cyclist and, in his late-20s, took up Scrabble. Warner, the Kiwi player, said Nigel played a game at his mother’s house, enjoyed it, and bought a set and a Scrabble dictionary. Over a few months, he inputted every word into a spreadsheet. “It was in very tiny print, had multiple columns per page, and numerical coordinates for rows and columns,” Warner said. “As he entered the words, they stuck in his memory. All of them. Then he joined the local club.”

Nigel won his first tournament easily; a write-up described him as “a promising young player.” A couple of months later, he signed up for a weekend tournament in Dunedin, more than 200 miles south of Christchurch. Nigel clocked out from his job on Friday afternoon, biked 14 hours overnight in the rain, went for a swim, won all 10 games with an average score of 512 points, and biked back in time for work on Monday. “We had offered to drive him home but he declined,” a longtime New Zealand player, Liz Fagerlund, told me.

In 1997, Nigel won the New Zealand national championship on his first try. Stories were passed around like whispered secrets: Nigel averaged 584 points in a tournament and 602 points in a club session. Nigel played six bingos in a row. Nigel threaded the 10-letter CHLORODYNE through the two Os and the E, with a blank Y. Nigel dropped SAPROZOIC around the international word ZO (a cross between a yak and a cow). He played GOOSEFISH, EPULATION, UROPYGIA.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” a perennial New Zealand champ, Jeff Grant, told me in Melbourne. “The word knowledge. The ability to pluck them out of nowhere.” After an unexpected victory, a New Zealand player who owned a T-shirt business designed one for himself: I once BEAT NIGEL RICHARDS. “Anyone could buy one, but only if they beat Nigel in a tournament,” Fagerlund said. “There weren’t too many.”

Nigel finished eighth in Melbourne. He would win his first world championship in 2007, and repeat in 2011, 2013, 2018, and 2019, when he won two world titles. He filtered out 100,000 or so international-only words and won the North American championship in 2008, and then four-peated from 2010-13. (No world championships were held in 2020-22 because of the pandemic. Nigel didn’t play in last year’s North American and world championships, held back-to-back in Las Vegas, and hasn’t played in the U.S. in six years.)

Nigel wears a blank expression during games. Arms parallel to the edge of the board, left hand folded over right, he stares unblinkingly at the tiles before making a play. In Melbourne in 1999, after winning a close, high-scoring game, a Canadian opponent said, “That was some of the most fun I’ve had playing Scrabble.” Nigel didn’t respond. He quietly verified the score, stacked some papers, reset the game timer, and began clearing up the tiles for the next round. “When I see you I can never tell whether you won or lost,” an American player said to Nigel. “That’s because I don’t care,” Nigel replied.

Outside the playing room, Nigel and I talked for 15 or 20 minutes. He wore aviator glasses and a T-shirt and jeans, his sandy hair combed forward. He had a rock-climber’s body and a bushy beard. Nigel told me he didn’t own a television, didn’t listen to the radio, didn’t read much, and didn’t have close friends. He was polite and matter-of-fact.

For most grandmasters, Scrabble is about the intellectual challenge of solving the puzzle contained in every rack of tiles. Emotions are a distraction. But Nigel’s word knowledge, his demeanor, his attitude, the way he genuinely seemed to eliminate outcome from the equation entirely—Nigel was different. “He’s got the gift, like no one I’ve ever seen before,” I wrote in my notes.

“I just enjoy trying to work out the possibilities and see what I can do, see what I can come up with,” he told me. “I can enjoy it if I win. I can enjoy it if I lose.”

“Are you ever disappointed?” I asked.

“No.”

“Honestly?”

“Why is there a reason to be disappointed? I’m just here for a bit of fun.”

The next year, Nigel moved to Kuala Lumpur. There were more tournaments with stronger competition and bigger prize pools in Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. (A local Scrabble player gave him a job.) By the time he left home, Nigel had won 85 percent of more than 600 games in New Zealand.

Scrabble was invented during the Depression by a laid-off New York architect named Alfred Butts. The game took off in the early 1950s, peaking with more than 4 million sets sold in a year. Chess and backgammon players identified familiar qualities in the new game—tactics, vision, knowledge, gamesmanship—and compiled lists of words. Tournaments started popping up in the early ’70s, and the first U.S. championship was held in 1978. Butts, in his later years, was mystified by players memorizing the dictionary. He thought he had created a wholesome family pastime, not a complex, cutthroat game worthy of mathematical analysis and tens of thousands of dollars in prize money that could spawn someone like Nigel.

After Nigel played (P)ERNOCTA(TED), an expert player had a Scrabble bot named Macondo play 10 million games against itself. Then he wrote a program to extract the number of bingos played by length. A nine-letter bingo occurred once every nine games, or 18 games per individual player, which isn’t especially rare. I played one in a tournament recently: ACROLEINS, through the C and O, an unusual word meaning a flammable liquid but also the plural of one of the 200 or so most-probable eight-letter words you can extract from a full bag of 100 tiles. I knew it from studying.

Words longer than nine letters are shooting stars. In the Macondo analysis, a 10-letter bingo came down once every 376 player-games and an 11-letter bingo once every 6,646 player-games. According to the Scrabble information website Cross-Tables, only six people have played more rated tournament games in North America than that. The bot has perfect word knowledge; non-Nigel humans wouldn’t know enough 11-letter words to plop down a theoretically available one even that frequently. (Long words that do get played tend to be common—including one last weekend in a tournament in Charlottesville, Va., where PERC, a chemical used in dry cleaning, was extended to PERCOLATING.)

“I could solve ACDEENOPRTT 100 times in an anagram quiz and never see the spot for it on that board,” Sokol, currently the top-ranked player in North America, who describes himself as a Scrabble influencer, said. “That’s part of the reason that I don’t study long words. So what if I know this word? I’ll probably never play it. And if I can possibly get into a position where it’s available, I would almost certainly not see it.”

He went on, “It is perhaps conceivable that if I was at least confident that PERNOCTATED was a word, maybe, just maybe, some amount of the time, if it was the only bingo in the position, I would spot it—and promptly retire from the game, because there’s no way I would ever find a better play for the rest of my existence as a Scrabble player.”

Anderson, who works on Scrabble products for Scopely Inc., maker of the game’s licensed app, put it to me this way: “Literally only Nigel could ever make this play. This is what separates him from everyone else. It’s not just his consistency. It’s the moves he makes that no one else can make.”

Like geniuses in other domains, Nigel is often compared to a computer, because of his mastery of the lexicon and his dispassionate comportment. In 2020, a Francophone world champion, Francis Desjardins, and a programmer named Gilles Blanchette built an engine designed to solve Scrabble endgames. Because Nigel “rocked us all French Scrabble players to our core,” Desjardins said, one of their first projects was to analyze his games. They collected 588 from various online sources.

The endgame starts when the last tile is plucked from the bag. At that point, Scrabble flips from a game of imperfect information—opponents don’t know each other’s tiles or what’s in the bag—to a game of perfect information—opponents know each other’s tiles because they’ve been marking off what’s been played on their scoresheets as the game progresses. Poker is a game of imperfect information; cards are hidden. Chess is a game of perfect information; nothing is hidden. Scrabble is both. The endgame is an effective way to evaluate player ability because it eliminates the randomness of the draw. There’s a quantifiable optimal sequence of turns.

Desjardins and Blanchette’s findings were astounding. In those 588 games, Nigel made a total of 11 errors in 919 endgame moves, or 1.2 percent of the time. Desjardins and Blanchette then examined the performance of Nigel’s opponents—but only ones who at some point had been ranked in the Top 10 in North America or the world. In those 298 games, the opponents made 202 mistakes in 432 moves—47 percent of the time. Nigel made a mistake once every 83.55 moves. The opponents made one every 2.14 moves. Nigel lost a total of 31 points from suboptimal play. The opponents lost a total of 1,818 points, in about half as many games.

But not only was Nigel superior to other grandmasters, he was also better than Quackle, an artificial intelligence–based Scrabble player and analyzer. Faced with the same 919 moves, Quackle made four times as many errors and lost seven times as many points as Nigel. “I do believe that no current player could ever reach Nigel’s level even if they had all the time in the world to train,” Desjardins told me. “It’s like trying to compete at basketball against someone who is 8 feet tall when you are only 5 feet tall.”

Sokol thinks such analysis may actually underestimate Nigel’s ability and potential. Unlike chess and other games, computers haven’t “solved” Scrabble. Math properties like probability and equity value are central to the game at the highest levels. But human behavior is, too. Players draw inferences from how long an opponent takes to make a move, or what tiles they’ve played and what they might have kept behind. Are they sitting on a blank? An S? A pile of dreck?

For most Scrabble players, clues like those influence almost every turn. Nigel’s moves, however, mimic a bot more closely than anyone else’s. Sokol said that indicates that Nigel doesn’t pay attention to external information or attempt to use his opponents’ weaknesses—including feeling intimidated across the board—against them. “If he started playing plausible-looking phony words from time to time,” Sokol said, “he would likely improve on his domination.”

David Eldar of Australia won the 2023 Scrabble world championship and $10,000 in a riveting seven-game final in Vegas that, as I recounted in Slate, turned on, of all things, a strategically brilliant play of a three-letter word. It was Eldar’s second world title and made him the only player other than Nigel with more than one. After the event, he wrote on his LiveJournal that he had “taken the lead in the 2nd best player race.”

The gap between Nigel and the rest of the field is huge. Since 1998, Nigel has won 76 percent of more than 4,000 career games sanctioned by the World English Language Scrabble Players Association. Eldar and the rest of the top five have won 68, 66, 67, and 66 percent, respectively, of their games. Eldar has outscored his opponents by a whopping 49 points per game. Nigel has outscored his opponents by 72 points per game. In Scrabble, a game in which luck sidles up to the board alongside skill, Nigel’s numbers beggar belief.

“I don’t know how to put this in layman’s terms,” Eldar said in an email when I asked about (P)ERNOCTA(TED), “but it essentially continues to confirm that he’s the best player at any game that ever existed. His brain extends leagues beyond the capability of a chess nerd who studied their whole life, for example. His unparalleled memory, spatial reasoning, and foresight is what differentiates him from me, or Magnus Carlsen, or (pick your champion)—he’s not human. No amount of practice or innate talent will ever render anyone normal to rival him.”

Other games have their outliers. Marion Tinsley lost a total of three games of checkers in more than 40 years of tournament play; in his book Seven Games: A Human History, journalist Oliver Roeder writes that a computer scientist who built a checkers bot discovered “to his creeping horror” that Tinsley hadn’t made a single mistake in more than 700 games. In backgammon, Masayuki Mochizuki of Japan is the only “Super Grandmaster” as judged by the Backgammon Masters Awarding Body, which uses computer models to rate performance.

Eldar mentioned Carlsen, the Norwegian chess grandmaster who has been the top-rated player since 2011 and, like Nigel, has won multiple world championships and dominated his peers. Studies have found that the ratings gap between Carlsen and his contemporaries is large, but on par with those of previous champions, including Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov. The debate over chess’s greatest of all time endures; depending on who’s talking, Carlsen is somewhere in the top five.

There’s no such debate in Scrabble. Two-time North American champ David Gibson had a winning percentage to match Nigel’s. But Gibson, who died in 2019, stuck to the more limited North American dictionary and was a methodical, defensive player. In addition to his lexical mastery, Nigel “spots every viable move within 10-20 seconds,” Eldar said. (Nigel told another player that he found PERNOCTATED in about 20 seconds.) He played just as fast in French—he has now won a total of five Francophone titles, and is believed to have memorized the entirety of that word list—and, as in English, made almost no mistakes. Given Scrabble’s complex board geometry and multiple competing options per turn, consistently and instantly identifying the best play is absurd. “Too bad he won’t tell us what’s going on,” Eldar said.

That’s the lament of every Nigel-curious Scrabble player: He doesn’t engage in the game the way other top players do. Nigel isn’t asocial. He dines with other players at tournaments and travels to visit and bike with fellow Scrabblers. “He has a great sense of humor—a great human being and a true friend,” an English player, Sumbul Siddiqui, told me. But he just isn’t interested in deconstructing or promoting the game. You won’t find interviews with Nigel in articles about him in ESPN, the Guardian, or the New York Times. (He didn’t respond to an email for this story.) He doesn’t rehash games with opponents. He doesn’t play online, doesn’t analyze his moves in Quackle, doesn’t post explanations of his thinking or detail his study habits.

At the awards ceremony after his first French championship, Nigel was asked if he had a specific method for learning the words. “No,” he replied. But there have been glimpses into his regimen. In 2011, Nigel told American expert Cecilia Le that he had indeed memorized everything through 15 letters; that he studied one hour a day (which isn’t much); and that he reviewed his word lists in alphabetical order. “I don’t want to miss one,” he said.

In Melbourne, I asked Nigel how he had learned so many words. He said he had read the two word-list books used at the time plus the 1,953-page Chambers Dictionary, on which the international Scrabble lexicon was then based. He said he scanned the dictionary looking at the words in boldface and later could conjure a snapshot of individual pages. “I can look at things and remember,” Nigel said. He had his spreadsheets, too. On bike rides he would recall the print images, like opening a document on a screen. Studying for Scrabble was “so boring,” he said. “The cycling helps.”

Did he have a photographic memory? “I think there are about 28,000 definitions of a photographic memory,” Nigel said. “I can recall images very easily, but I can’t put the image in a context. I can remember a picture, but I can’t remember where I’ve seen it. I just have to view the word. As long as I’ve seen the word, I can bring it back. But if I’ve only heard it or spoken it, I can’t do it at all.” I asked how he did it. “I’ve wondered lots about it but I haven’t figured out the answer,” he said. (Today, Nigel appears in Wikipedia’s “List of people claimed to possess an eidetic memory.”)

Warner, the New Zealander, told me that the first few times he played him, Nigel’s eyes “seemed to do a rapid scroll in his head” before making a move. “That’s when I first thought, this guy is a computer,” Warner said. “He later told me that he would see the coordinates from his self-compiled lexicon before the word appeared in his brain.” Nigel would look at the board, look at his rack, and his brain did the rest.

A quarter-century later, not much about Nigel seems to have changed. His beard, which for a time cascaded to his chest, is trim and flecked with gray, but he still wears oversized glasses and a bowl cut. He’s still an avid biker; after winning the Bangalore tournament with a 24-8-1 record, he accepted his trophy wearing a T-shirt given to him by another player that read “Cycopath.” According to players who know him, Nigel still doesn’t watch TV, doesn’t have a smartphone or home wifi, and no longer works. “He’s really the only person in the world who has truly earned his livelihood from tournament Scrabble,” Gerry Carter, a player from England who lives in Bangkok and has known Nigel since the 1990s, said.

And he’s still thought to look at his word lists about an hour a day. “He has told me that he needs to study regularly to keep all the words in his brain,” Carter said. After conquering the game in French, Nigel told Carter he was considering Spanish. Carter suggested trying Kham Khom—Scrabble in Thai, which has a script of more than 40 consonant symbols and 30 vowel forms. “He said he might one day,” Carter said.

After one of his championships, Nigel was asked for the secret to his success. “I’m not sure there is a secret,” he replied. “It’s just a matter of learning the words.” Which is true. Once you learn literally all of the acceptable words—and can almost always find the right one in the right place under time pressure in a game—anything is possible. It’s just that no one else has proven capable of doing that. (For the record, Nigel does occasionally lose. At the 2018 North American championship in Buffalo, another Scrabble legend, Joel Sherman, beat Nigel three straight times to win his second continental title to go with one world championship.)

Scrabble players and writers have described Nigel with words such as ascetic, monklike, or indifferent. I think he’s actually more like Alex Honnold climbing El Capitan without a rope: preternaturally calm, prepared for any circumstance, focused only on what comes next. Unless he’s hiding something, Nigel doesn’t consider any of what he’s accomplished to be noteworthy. Not his unmatched collection of championships. Not his career earnings, which are hard to pin down but north of $300,000. Not even his feats of anagrammatic wizardry.

Players told me that if one of Nigel’s pedestrian bingo options in Bangalore had scored even one point more than (P)ERNOCTA(TED), he almost certainly would have eschewed the once-in-a-lifetime, hang-it-in-the-Louvre, proof-of-God’s-existence move. “To him, PERNOCTATED was probably just like any other bingo he’s ever played,” said Jeremy Khoo of Singapore, a doctoral student in philosophy at Princeton who competed in Bangalore.

The final score of the game was 748-301. It was Nigel’s highest tournament score ever. (P)ERNOCTA(TED), Khoo said, “doesn’t tell me anything new about what Nigel can do, since we already know that he’s capable of these things. But it’s still stunning when it happens.” Afterward, another player asked Nigel if he knew the meaning of the word. Nigel didn’t miss a beat. “The past tense of pernoctate,” he said.